How do people depict skin tones in photography and what messages can photographs that focus on the skin convey? “Melanin Matters” was a photography workshop on skin and skin tones jointly organised by the CRC 1482 Human Differentiation, the Goethe-Institut Nigeria and the Nlele Institute. It took place in Lagos from October 29 to November 5, 2024, and was inspired by Marion Grimberg’s PhD research on skin tone differentiation.

Throughout the workshop, participants explored how they perceived and thought about skin and skin tones and how photography can influence these perceptions. They were also given time to develop their own photography projects. Two experienced photographers provided insights into using different light sources in photography and gave advice on how to work with models of different skin tones. They further offered guidance on storytelling and discussed the influence photographers have in shaping public perceptions of, for example, beauty.

For their personal projects, the participants formed sub-groups based on their ideas and interests. One group focused on scars and scarification, another on beauty practices. The final group explored the topic time’s influence on the skin. We are delighted to present some of their results in this digital exhibition.

Scars & Scarification

The group working on scars and scarification reflected on the way our experiences and beliefs shape our bodies. Some scars, although accidental, tell a story about their bearer. Certain professions, such as boxing, leave visible marks on the body over the years. Some Muslims develop a dark mark on their forehead after years of daily prayer. These marks, in turn, influence how those who bear them are categorised by others, for example as violent or devout. Other markings, such as scarification and tattoos, are intentional and can give insights into the social categorisation of the bearer. Scarification, for instance, can show ethnic affiliation or serve as a sign of belonging for members of a religious or spiritual group.

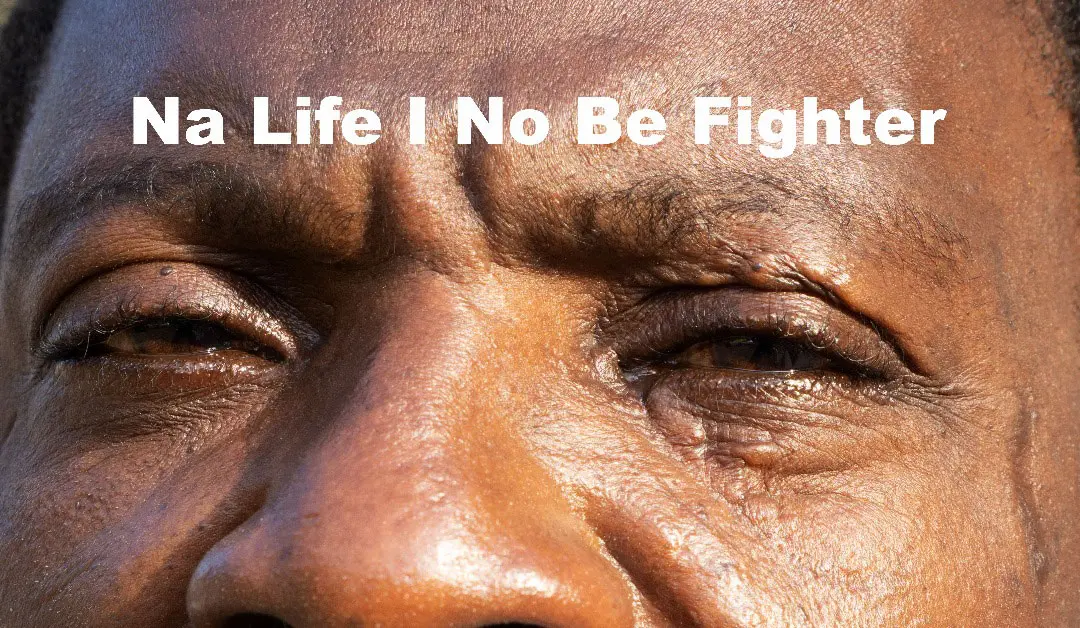

Hassan O. Abiodun

This image by Hassan O. Abiodun shows an elderly man who has noticed that he is often viewed as dangerous or tough because of his scars. He does not, however, agree with this categorisation. Instead, he explains that life has marked him (‘na life’ means ‘it is life’ in Nigerian Pidgin) and that he is not a fighter (‘I no be fighter’). A photograph taken from a wider angle then shows the black mark on his forehead, indicating that he is a devout Muslim: Years of five daily prayers have left their mark on his face. Zooming out enabled Abiodun to shift what the viewer sees and perceives the portrayed man (dangerous versus devout).

Kayode Oluwa

Another project that focused on scars is that of Kayode Oluwa, who portrayed boxers from Lagos. By its very nature, this profession leaves marks on the body. Oluwa wanted to show this by zooming in on typical boxing scars. His images show scars on the eyebrow and around the eye, as well as hardened skin on the knuckles, left by the practice of punching.

Neec Nonso

Neec Nonso calls his work ‘in the in in’. He describes it as a meditation on the Black body as a vessel of pain, resilience and survival. By carving scars into photographs of his brothers, Nonso explores the hardships Nigerians endure, from economic struggles to social injustices. These marks, inspired by comments his brothers have been confronted with, reflect the burdens they carry and the strength they possess. For Nonso, Black skin, a testament to both suffering and enduring, is a shield and a target, a canvas upon which stories of struggle and resilience are inscribed. Through his images, he honours the courage it takes to carry on, acknowledging that survival is not just about enduring but also about transforming.

Beauty

The group focusing on beauty looked at skin and skin tone from a different angle: What are Nigerian standards of beauty, and how do they relate to self-worth? What is commercial beauty? Are there different ways of perceiving beauty?

Oyewole Lawal

Oyewole Lawal’s project addresses skin lightening. To lighten their skin, consumers apply skincare products such as those in Lawal’s photographs. This practice is common in Nigeria but can have harmful consequences. Lawal’s goal was to document the narrative surrounding the creams. His project aims to provoke reflection on how advertising and social norms influence perceptions of beauty.

In this series of photographs, he shows skin-lightening creams next to the darkened knuckles. Such darkened knuckles are a common side effect of skin lightening with the chemical hydroquinone. The images in his ‘Triptychs’ series show the promises of perfect beauty that appear on the packaging of the products. One product claims, ‘Precious Perfect Lotion is specifically designed to give perfect beauty. A true treasure for Black and mixed skins. Composed of fruit acids and radiance white, it ensures a gradual, rapid and long-lasting lightening of your skin. Blemishes fade, unifying your skin tone while moisturizing and nourishing at the same time, with a final result of scented soft glowing skin. For all skin types.’

The packaging of the Caro White cream features a stamp from the National Agency for Food and Drug Administration and Control (NAFDAC). By including this, Lawal aims to point at the regulation of skin lightening products which he deems as insufficient and that exposes Nigerians to health risks.

Mecca Akello

Mecca Akello also reflected on skin tone and skin lightening in her project ‘Shades of Worth’. The project is a visual exploration of beauty, identity and self-worth in a society where lighter skin is often equated with desirability and success. Through a series of self-portraits, she confronts and deconstructs the pervasive standards that elevate one skin tone over another, challenging the ingrained belief that beauty is defined by complexion. She draws inspiration from the slogans of skin-lightening products such as ‘White is Purity’, and ‘Glow Brighter, Shine Whiter’, which urge individuals to alter their appearance.

Using bold colours, layered textures and juxtaposed images, she interweaves local notions of beauty with the lived experiences of those who feel compelled to conform. The themes of lightening and illumination recur throughout the work, symbolising the internal conflicts many experience – between self-acceptance and societal expectations.

Simeon Ayodele Samuel

As a photographer, Simeon Ayodele Samuel has always been fascinated by how images can shape perceptions and social norms. He believes that the ideals promoted on social media, in advertising and in film create unattainable standards. They shape standards of beauty that can affect self-esteem and identity. His project celebrates the diverse beauty within the Black community. It is a visual exploration of the rich spectrum of skin tones, facial features and body types that he encounters in Nigeria.

For his Melanin Matters project, he selected images before and after editing to show the unattainability of beauty standards set by magazines and advertisements.

To learn more about the preference for lighter skin in Nigeria as well as skin lightening and its side effects, please check out the panel discussion and podcast episode linked at the bottom of this digital exhibition.

Skin & Time

Our skin is our largest organ and is used to differentiate people in many ways. For example, being Nigerian is associated with being Black, while having fair skin is considered a sign of femininity, beauty and wealth in Nigeria. Skin is also a marker of age as it loses elasticity over the years.

Odunayo Odedoyin

Odunayo Odedoyin dedicated her project to the theme of ageing. By contrasting close-up portraits and hands of younger and older people, she aims to show both the physiological differences between generations and how environment and lifestyle affect the skin. The project explores the relationship between time, the body and the inevitable effects of ageing.

She interprets ageing in two ways: Firstly, as a physical change caused by time, genetics and external factors such as lifestyle and sun exposure, and secondly, as a sign of resilience and a person’s history inscribed in the skin. She urges us to embrace, rather than fear, the natural journey of ageing.

Ololade Lawal

In contrast, the project by Ololade Lawal looks at the subtle changes in children’s skin over the course of a single day.

Noah Misan Okwudini

Noah Misan Okwudini uses his project to tell a fictional story about an ageing scientist. Driven by existential angst and the ambition to reverse the effects of ageing, he embarks on a daring experiment with a willing (younger) participant. Together, they make a breakthrough that has unforeseen consequences, causing him to become the first of the ‘Melanin Synthes’.

Okwudini’s story explores themes of ageing, bodily transformation and the ethical complexities of human enhancement. It raises questions about the boundaries between human and post-human, natural and artificial, and examines the ethics of extending life and preserving youthful skin. Ultimately, it reflects on human identity in the face of (bio)technological progress.

Okwudini was inspired by the research project Posthuman Dedifferentiation? within our CRC 1482 Human Differentiation thereby connecting two types of human differentiation in his project.

Glimpses at Coloristic Human Differentiation. A Commentary by Marion Grimberg

As the visible surface of the human body, the skin is subject to cultural ascriptions and manipulations. The photography projects of the Melanin Matters week beautifully illustrate this. The pictures presented above show a variety of meanings that are associated with skin and skin tone in Lagos, Nigeria. In doing so, they highlight some of the themes addressed by our research project on Coloristic Human Differentiation that examines the (de)thematisation, meaning and presentation of skin colour in everyday life, both in Nigeria and elsewhere. Our research project aims at developing a post-racial reconceptualisation of skin colour as a flexible marker of human categorisation and seeks to understand how and when skin tone becomes a marker of, for instance, ethnicity, class, gender, attractiveness, health or disability. In the following paragraphs, I am commenting on a selection of the photography projects, reflecting on them through the lens of our research project.

Kayode Oluwa’s photographs exemplify how the practice of boxing and the bodily work of boxers can leave traces on the body. A boxer can identify a fellow boxer by physical markers such as scars around the eye and rough knuckles. In Oluwa’s work, signs that are inscribed on the skin serve as markers for a form of athletic human differentiation. His project can also be linked to a sociological theory from 1995. The rough, hardened knuckles of the boxers in Oluwa’s photographs recall the bodily capital that Wacquant elaborated upon in his essay ‘Pugs at Work: Bodily Capital and Bodily Labour Among Professional Boxers’. Working with professional boxers in Chicago, he noticed that their bodies were central to their work. In addition to the three types of capital that Bourdieu identified in ‘Forms of Capital’ (1986) – economic capital, social capital and symbolic capital – their bodies seemed to represent a fourth form of capital. Alongside assets such as their network (social capital) and awards (symbolic capital), it was above all their bodies that gave them access to economic capital, i.e. financial rewards. Not only was physical effort required during a fight, but Wacquant noticed that the boxers were constantly working on their bodies in between fights. This work on the body was a central part of the boxers’ reality and everyday life. They tried to maximise their performance through training. In doing so, they had to be careful not to overdo it and suffer the injuries typical of their sport, such as a broken knuckle or hand. They also tried to boost their bodily performance before a fight through diet management and sexual abstinence so as to increase their chances of converting bodily capital into economic capital.

While some projects focus on scars, others zoom in on the marks that time and ageing leave on the skin. Odunayo Odedoyin’s photographs juxtapose images of the hands and faces of ‘young’ and ‘old’ Nigerians. This illustrates how time inscribes itself on the skin and how the skin can be used as a marker to categorise people by age: The observer categorises a person as ‘young’ or ‘old’ by evaluating aspects of the skin, such as its wrinkles or firmness.

Noah Okwudini’s photo story explores body modification and the limits of what is human by telling a tale of transformation: An ‘old’ scientist slips into a ‘young’ shell and becomes a new, post-human being. The new shell is symbolised by a ‘young’ man with firm and wrinkle-free skin. What is interesting about this photo story is that the scientist’s transformation leaves a trace: The new post-human being has silver-shining skin. It raises the question of the limits of body enhancement by inscribing the transformation into the protagonist’s body and asks: Can we reinvent ourselves without leaving a trace of what was before?

Unwanted side-effects from attempts to modify one’s body also come to light in Oyewole Lawal’s work. Lawal shows how people who have lightened their skin can end up with the stigmatised marks typically associated with skin lightening. While some skin lightening practices may go unnoticed, side-effects are common among users of skin lightening products, especially when the products are used over a long period of time. Lawal chose to place images of the product packaging against the user’s hands. The darkened knuckles visible in the images are a typical side effect of hydroquinone, a chemical found in many skin-lightening products. They are an example of how attempts to modify the body can backfire. Skin lightening is a common but socially frowned upon practice in Nigeria. The knuckles show how the attempt to increase one’s social standing through lighter skin can have the opposite effect, i.e. how lightened skin can lead to stigmatisation instead of appreciation. It also addresses how the skin, as malleable as it is, can act against the will of its bearer, raising questions about the agency of the skin.

Olalade Lawal proposes a less common temporal contrast by showing morning and afternoon portraits of children. She demonstrates how one and the same person can have different skin depending on the context and circumstances. Considering this, how can we make statements about someone’s skin, when its texture, health, colour etc. is variable and highly dependent on aspects such as skin care, lifestyle or sun exposure? Skin not only changes over the years but is influenced by a multitude of other factors, leading to differences that can be observed over much shorter time spans. In our research project Coloristic Human Differentiation, one challenge in speaking about skin tone lies in its definition. When we speak about humans, do we portray them as having only one skin tone? If so, where do we find/locate it on the body? While people who regularly tan may see the sun-exposed parts of their body as representative of their ‘natural’ or ‘true’ skin tone, those who try to avoid tanning may refer to skin untouched by the sun as representative of it.

Neec Nonso and Mecca Akello make the invisible visible in their projects, choosing to address issues that lie beneath the surface through photographs that highlight the skin. Nonso used the material surface of printed photographs to carve into the skin of his depicted models. To show how he sees the Nigerian experience as being characterised by suffering and hardship, he marked the skin in portraits of his brothers. The results are X-ray-like images that bring internal scars and wounds to the surface, and thus to light.

Akello, as a darker-skinned woman, uses self-portraits to reflect on the ideals of beauty to which she has been subjected. Starting from her own skin, she provides a socio-cultural commentary and asks what beauty is in the Nigerian context – a question also raised by our research project on skin tone-based human differentiation. Her self-portraits explore how beauty is linked to lightness of skin: ‘But what is beauty’ shows the psychological distress caused by the slogans and names of lightening products. Other images show her drinking bleach, getting lightening injections, and scrubbing off her skin in an attempt to conform to the beauty ideal of skin-lightness. She starts and ends her series with images about advertising, beginning with the messages communicated by lightening products and ending with the place (or lack thereof) of darker-skinned women in advertising. She feels that darker-skinned women are underrepresented in the public space and in advertising. Through her self-portrait, she engages with the pain of feeling like it is not her place to be seen, to be in the spotlight. Akello’s photographs beautifully visualise central themes of our research project, namely what meanings are associated with skin tones in Nigeria, how they connect to other categorisations like gender and, lastly, what consequences there are on a personal and on a societal level of sorting individuals into skin tone categories.

Marion Grimberg is a PhD candidate in social and cultural anthropology and a member of the research project Coloristic Human Differentiation.

Literature

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1986. ‘Chapter 1: Forms of Capital.’ In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education, edited by J. Richardson, 241–58. Westport, CT: Greenwood.

Wacquant, Loïc J.D. 1995. ‘Pugs at Work: Bodily Capital and Bodily Labour among Professional Boxers.’ Body & Society 1 (1): 65–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357034X95001001005.

Further Information

If you want to find out more about skin tone differentiation in Nigeria we recommend our panel discussion "Living in your own skin".

Together with five panelists from the fields of dermatology and entertainment, Marion Grimberg discusses the state of skin health and skin tone-related discrimination in Nigeria. They discuss current skincare trends and their possible dangers and talk about the differential treatment people experience in Nigeria based on their skin tones.

You can also listen to our Podcast "Sone & Solche".

In Episode 18 "Melanin Matters I" Marion Grimberg and Olabanke Goriola discuss light-skin privilege, skin lightening, and the difference between the concepts of colorism and skin tone differentiation. Dermatologist Dr. Folakemi Cole-Adeife offers input on the state of skin health in Nigeria.

Episode 19 "Melanin Matters II" focuses on the connections between skin tone, class and gender.

Contact

Design and technical implementation of this site: Mainz University Library, website@ub.uni-mainz.de